Казино Х – Вход и Регистрация в Casino X

Casino Х официальный сайт ворвался в индустрию онлайн гемблинга 12 лет назад. Компания появилась на слуху гемблеров в 2012 году и с момента официального релиза фиксирует стабильный рост числа зарегистрированных клиентов. На данной платформе пользователи получают классные возможности на хороший заработок, а также гемблинг бесплатно ради удовольствия.

На сегодня Казино Х официальный сайт предлагает следующие преимущества посетителям и бетторам, успевшим открыть учетную запись:

- Бесплатные ставки. Демонстрационный режим доступен всем пользователям, независимо от наличия зарегистрированного аккаунта.

- Удобная регистрация. Вы можете пройти открытие счета традиционным путем или через привязку социальных сетей.

- Портфолио для гемблинга. Компания славится огромным выбором не только среди игровых автоматов, но и live casino и столов.

- Бонусы. Проект запускает промоакции за регистрацию, размещенные ставки с возвратом, сопровождает бетторов подарками за внесение депозитов и другие.

- Лицензия. За деятельностью казино икс следит регулятор Кюрасао, что повышает доверие пользователей данной платформе.

- Мобильное приложение. Игорное заведение предлагает гемблерам удобный процесс ставок не только в мобильных браузерах, но и через собственное программное обеспечение на iOS и андроид.

- Защита и безопасность. Компания регулярно использует лучшие системы безопасности и шифрования информации.

Официальный сайт Казино Х

Казино Х официальный сайт предлагает юзерам отличную навигацию и расположение элементов, к дизайну и интерфейсу площадки быстро привыкнут даже неопытные бетторы. В верхней части страницы найдете опции для логина в аккаунт и создания учетной записи, кликабельную возможность изменения языка и меню с игровыми кейсами. На основной странице представлены баннеры с информацией о потенциально крупном профите в заведении благодаря бонусам и турнирам.

Казино X предлагает круглосуточную поддержку через лайв чат, эта опция при навигации всегда активна с правой стороны. На главной странице представлены главные опции для гемблинга live дилеры, казино и бонусы. В футере компании в один клик откроете правила и условия, материал по ответственным ставкам, защиту информации, все доступные методы коммуникации с представителями бренда и перейдете на каналы клуба в социальных сетях. Внизу вашего экрана всегда будут отображаться последние крупные выигрыши гемблеров в ассортименте заведения.

Дополнительно, в футере Казино X интегрированы логотипы провайдеров, чьи решения по слотам и лайвам внедрены для активации ставок и принимаемые клубом способы платежей для депозитов и выводов средств.

Casino X зеркало

Ведущие платформы в индустрии делают все, чтобы не останавливаться на текущих достижениях, несмотря на возможные ограничения в работе. Лимиты в деятельности online ресурсов для азартных развлечений устанавливаются в странах, где вводятся законы и запреты на ставки в наземных клубах и в интернете. Если основной ресурс заблокирован, то пользователям предлагается отличная альтернативная возможность на доступ к играм и денежным средствам через Казино икс зеркало.

На сегодня зеркало это дополнительные домены от бренда, в которых игрокам предоставляется аналогичный опыт использования всех функций основного сайта. Важно знать, что в сети есть мошеннические площадки, которые за основу берут дизайны и интерфейсы знаменитых и популярных платформ. Казино Х актуальное зеркало следует уточнять у следующих источников:

- Саппорт. В режиме 24/7 вы можете активировать переписку со специалистами лайв поддержки и задать вопрос относительно рабочей ссылки на зеркало. Вам ответят в течение нескольких минут и подробно предоставят всю необходимую информацию.

- Социальные сети. У компании большое комьюнити в социалках. Для поддерживания коммуникации и активных действий клиентов специалисты размещают различные бонусы, оповещают о новых турнирах и постят информацию относительно зеркала Casino Х.

- Партнеры. Не будет лишним поинтересоваться, с кем сотрудничает заведение. Но здесь вы рискуете стать жертвой фейковых ресурсов, поэтому отдавайте предпочтение вышеприведенным двум вариантам для уточнения кейса.

Казино X вход и регистрация

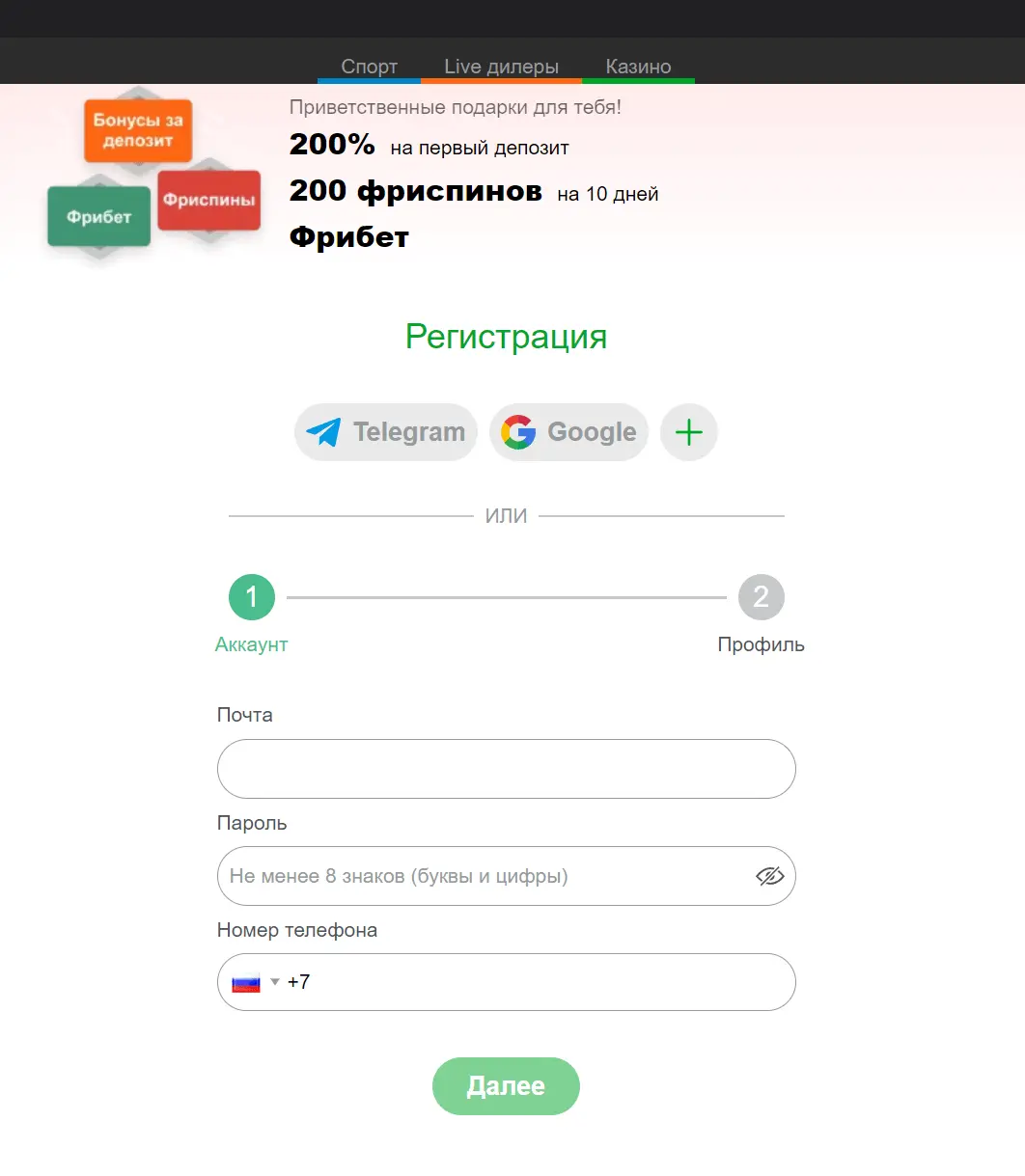

Чтобы получить возможность покрутить барабаны слотов с бонусами, участвовать в захватывающих турнирах и стать одним из претендентов на срыв крупных джекпотов, вам нужно пройти легкий процесс открытия учетки. Казино Х регистрация запускается нажатием соответствующей кнопки в верхней части экрана (выделена ярким оранжевым цветом). Система перенаправит пользователя на новый интерфейс, где нужно выполнить следующие действия:

- Ввод актуального адреса электронной почты;

- Указание рабочего номера телефона;

- Ввод пароля.

Это шаги для стандартной процедуры создания профиля, которая отнимет у вас пару минут. Есть более быстрый метод присоединения к платформе посредством привязки аккаунта соцсетей или гугл-почты. После завершения Casino Х регистрации вы можете авторизоваться в профиль и ознакомиться со всеми опциям в личном кабинете:

После входа в Casino Х можете по желанию верифицировать созданный профиль. Сама компания не требует обязательной идентификации личности, но процесс могут запустить в целях безопасности, а также при крупном выигрыше в ассортименте гемблинга.

Бонусы онлайн казино Казино X

На данной платформе действует замечательная бонусная программа, в которой игрокам предоставляются привилегии и повышенные шансы на выигрыш с использованием подарков. Выполнив Казино Х вход, пользователь автоматически претендует на получение бонусных средств. Новички на ресурсе могут забирать 200% на сумму первого депозита. В рамках приветственного пакета клиенты активируют фриспины в слоте The Dog House это хит от разработчика Pragmatic Play.

На еженедельной основе гемблеры с активным профилем будут забирать кэшбэки, если будет зафиксировано больше поражений. Максимальный процент возврата составляет 15%, на него будете претендовать после достижения уровня Ultimate. Говоря о статусе, Казино Х дает отличную VIP-программу лояльности, где будете активировать лучшие бонусные опции.

Игры Casino-X

Игровые решения на этой площадке разработаны для двух сегментов бетторов новичкам и опытным пользователям. Первые могут играть без риска потерь собственных денежных средств, включив демонстрационный режим в слотах. Вторые ставят с реального баланса в слотах, на сотни вариаций наиболее популярных решений с лайв ведущими и дилерами. Всегда можно участвовать в промо-событиях, лотереях и турнирах и увеличивать шансы на крупные призы.

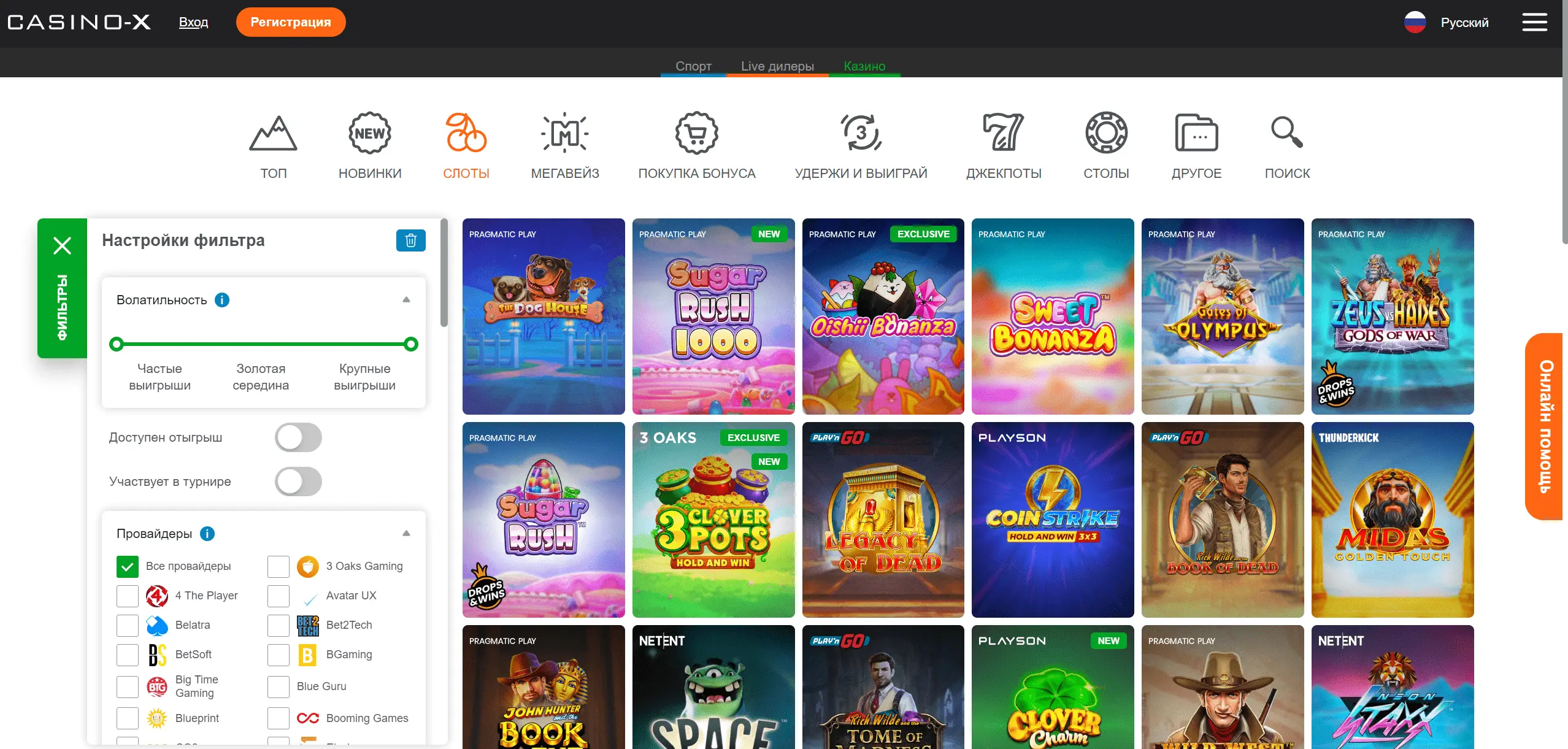

Слоты

На сегодня Casino Х слоты представлены от 53 известных и надежных разработчиков программного обеспечения. Тематика на любые предпочтения участников (аппараты с животными до мистического геймплея). В данном клубе хорошо позаботились об удобстве поиска необходимого игрового решения на основе функций в процессе ставок. Вы можете быстро найти слоты с использованием многочисленных фильтров. Игровые автоматы доступны для бесплатного гемблинга, а также с использованием ваших средств на реальном счете.

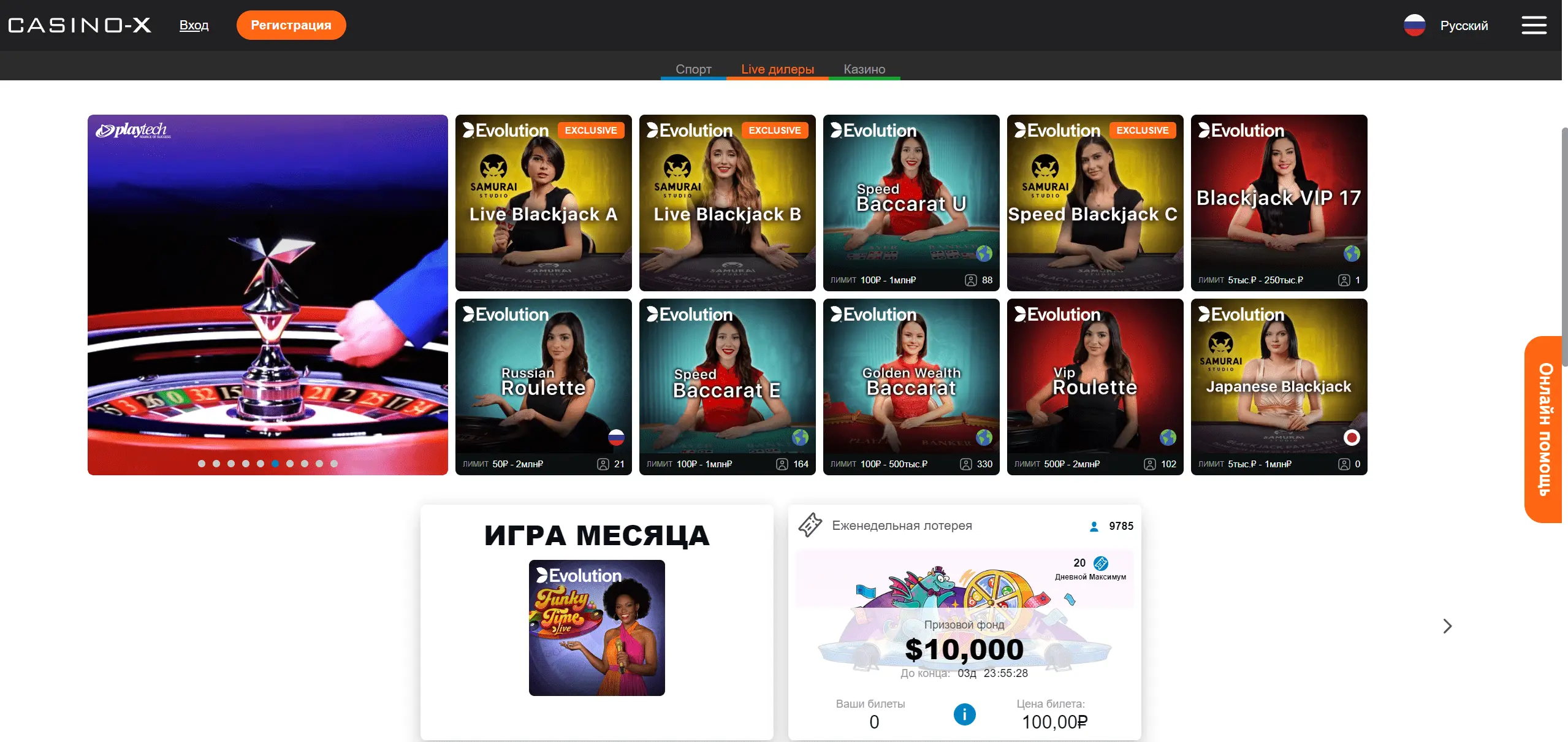

Лайв игры и столы

Вы увидите все доступные для бетов предложения после перехода по опции лайв дилеры с основной страницы. Вас встречает горизонтальное меню с онлайн играми, рулеткой, баккарой, блэкджеком и игровым шоу. В настройках Казино Х интегрировало такие опции для поиска, как желаемые диапазоны ставок, разработчики и доступные позиции для входа в игровой процесс. Самые популярные классические столы идут в многочисленных вариациях в зависимости от провайдера.

Аркады

Эту часть также можно назвать относительной новинкой в онлайн азартных развлечениях. Увидеть актуальную коллекцию тайтлов можно нажатием на опцию «другое» в игровом меню. В этом разделе портфолио откроете скретч-игры, запустите космонавта в Spaceman, поставите на Хай-Ло, плинко, футбол-скретч и многое другое.

Вывод средств с личного счета

Благодаря лицензии Кюрасао online Casino Х пользуется большим спросом среди игроков, которые не переживают относительно своевременного получения выплат. В личном кабинете вам необходимо открыть вкладку с финансами и выбрать опцию с выводом. Клиенту нужно выбрать платежное средство (банковские карты, крипта или электронные кошельки), указать сумму перевода, реквизиты для трансфера и кликнуть на «получить».

Быстрее всего сумма поступит на криптокошелек. Со своей стороны администрация заведения старается быстро подтверждать заявки как на снятие, так и на пополнение счета.

FAQ

Как выигрывать на сайте Казино Х?

Вам нужно приложить определенные усилия, чтобы иметь лучшие шансы на выигрышные игровые сессии. Сначала почитайте правила и положения по ответственной игре. После – попробуйте бесплатные ставки с виртуальными кредитами от казино, чтобы выбрать слоты с лучшими процентами возврата от бета. Далее откройте профиль и обязательно используйте фриспины и подарок на первый депозит для дополнительного профита. Участвуйте в турнирах, где установлены минимальные требования для входа. Ответственный и разумный гемблинг – ключевые критерии для всех пользователей.

Как получить промокод на Casino Х?

Бонус коды можно спросить у службы поддержки в чате, который оперирует в круглосуточном режиме. В футере страницы найдете рабочие ссылки на социальные сети проекта, в публикациях нередко разыгрывают промокоды для клиентов.

Как зайти на Казино Х?

Нужно открыть любой браузер (с компьютера или смартфона), в поисковике написать название клуба и перейти по первым ссылкам в выдаче. Не исключается, что игорное заведение может быть заблокировано в вашем регионе. В таком случае попробуйте включить сервисы VPN или перейти на рабочее зеркало, в котором получите полностью аналогичный основному ресурсу пользовательский опыт.

Отзывы

Одно из топовых казино по фильтрам. Реально очень удобно находить игры с такими прекрасными возможностями.

Всегда ставлю только в слотах, Казино Х не разочаровывает и регулярно сообщает мне о новых пополнениях в играх.

Хороший сайт, но мне не понравился дизайн в мобильной версии, неудобно пользоваться.

Остался недоволен службой поддержки. Вроде написал в позднее время, когда по идее не должно быть много игроков, но отвечали очень долго.

Отличные турниры! Несколько раз мне подарили фриспины за активное участие и оповестили о бонусе по почте.